Overview of Gandhara Music

- Türán

- May 23

- 5 min read

Instruments and Practices of Gandhara Music

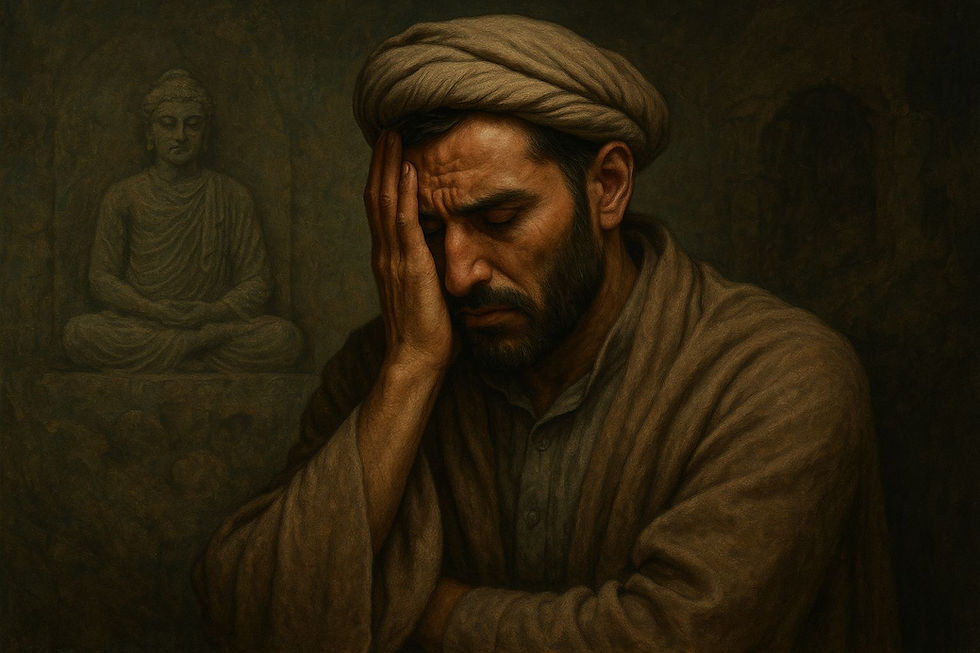

Gandhara, in modern Pakhtunkhaw was a cultural crossroads where music likely mixed Greek, Persian, and Indian styles. Art from the 1st to 5th century CE, like reliefs at Taxila and Swat, shows musicians playing lutes, flutes, and percussion, suggesting music was key in Buddhist ceremonies and courtly life.

Instruments and Practices of Gandhara Music

Depictions include short-necked lutes (ancestors to modern lutes), double flutes (like the Greek aulos), and hand drums. These were used in rituals, with chants and melodies aiding meditation, as seen in Gāndhārī texts.

Link to Pashto Music

Pashto music, rich in the Pashtun regions, uses the Rubab, a lute-like instrument, which research suggests may have evolved from Gandharan lutes. Other instruments like flutes and drums show continuity, reflecting a shared heritage.

Survey Note: A Profound Exploration of Gandhara Music and Its Link to Pashto Traditions

Gandhara, an ancient region spanning modern Pakhtunkhaw was a vibrant cultural crossroads from the 6th century BCE to the 11th century CE, particularly flourishing under the Kushan Empire (1st to 5th centuries CE). Its strategic location facilitated the blending of Greek, Persian, Indian, and Central Asian influences, making it a fertile ground for artistic and musical innovation. This article delves into the musical traditions of Gandhara, as evidenced by archaeological and artistic records, and explores their profound connection to contemporary Pashto music, reflecting the enduring legacy of this cultural heritage.

Historical Context and Cultural Significance

Gandhara's historical significance is rooted in its role as a trade and cultural hub along the Silk Road, connecting South Asia to Central Asia and beyond. The region, encompassing areas like Taxila, Swat, and Peshawar (ancient Puruṣapura), was a center for Buddhism, with monasteries and stupas adorned with intricate art. This art, known for its Greco-Buddhist style, often depicted musicians, providing a window into the musical practices of the time. The Kushan dynasty, particularly under rulers like Kanishka, patronized Buddhist art and culture, fostering an environment where music was integral to religious and secular life.

Archaeological Evidence of Musical Instruments

Archaeological findings from Gandhara, such as reliefs at Butkara I in Swat and Sirkap in Taxila, reveal detailed depictions of musicians playing various instruments. These sculptures, dating from the 1st to 4th century CE, show stringed instruments like short-necked lutes, wind instruments such as flutes (including double flutes similar to the Greek aulos), and percussion instruments like hand drums and cymbals. A notable example is a frieze from the 2nd to 4th century CE, described as featuring "dancers with swaying hips, double flute, hand percussion, and a Lyra, held in a heavy-metal guitar-like gesture". These depictions, crafted in schist and stucco, highlight music's role in both ritual and courtly settings.

Detailed Description of Instruments

The short-necked lutes in Gandharan art, as noted by musicologist Curt Sachs, have a pear-shaped body, short neck, frontal stringholder, lateral pegs, and typically four or five strings, played by plucking. These are considered ancestors of modern lutes, including the Rubab. The Lyra, a small harp-like instrument of Greek origin, is also depicted, reflecting Hellenistic influence. Wind instruments include flutes, with representations in Greco-Buddhist art at Gandhara, as mentioned in Nad Sadhna, and double flutes, likely akin to the aulos. Percussion, such as hand drums and cymbals, provided rhythmic accompaniment, often seen in dance scenes, suggesting their use in festive contexts.

Cultural Influences on Gandharan Music

Gandhara's music was a synthesis of diverse influences. Greek elements, introduced after Alexander the Great's conquests, are evident in the Lyra and aulos, while Persian and Central Asian traditions contributed to the development of lutes and drums. Indian influences, with instruments like the veena and flutes, are also apparent, as seen in the broader Indian musical tradition. This cultural fusion is reflected in the iconography, where musicians are shown in both Buddhist and secular settings, blending local and foreign styles.

Music in Gandharan Society

Music in Gandhara was deeply embedded in religious life, particularly within Buddhist monasteries. Chants, accompanied by flutes and drums, were used in rituals, as evidenced by Gāndhārī Prakrit texts, the oldest Buddhist manuscripts from the 1st century CE. These chants, designed for oral memorization, had rhythmic and melodic structures, as noted by Xuanzang in the 7th century. In secular contexts, music was part of courtly entertainment, with reliefs showing musicians at royal courts, indicating its role in social and festive gatherings.

Evolution of Instruments and Practices

The instruments depicted in Gandharan art evolved over centuries, influencing regional music. The short-necked lutes are seen as ancestors of modern lutes, including the Rubab, a key instrument in Pashto music, as suggested by Sachs. Flutes and percussion instruments, such as drums and cymbals, have continued in various forms, with evidence of continuity in the region's musical traditions. This evolution reflects the dynamic cultural exchanges that characterized Gandhara, with instruments adapting to local needs and aesthetics.

Introduction to Pashto Music

Pashto music, the traditional music of the Pashtun people, is a vital expression of their cultural identity, spanning Afghanistan and Pakistan, including areas once part of Gandhara. It encompasses genres like Tappa, Charbetta, and Shaan, often accompanied by poetic lyrics reflecting daily life, love, and valor. Music is integral to Pashtun gatherings, from weddings to hujrahs (community spaces), with instruments playing a central role in maintaining cultural continuity.

Instruments in Pashto Music

The Rubab is the most prominent instrument in Pashto music, a lute-like stringed instrument with a deep, resonant sound, often used solo or in ensembles . Other instruments include the Mangay (a clay pot drum), Tabla (hand drums), Harmonium (keyboard with reeds), and flutes, as noted in Voices of Afghanistan. These instruments create the distinctive melodic and rhythmic texture of Pashto music, blending tradition with modern adaptations.

Linking Gandhara to Pashto Music

The geographical overlap between ancient Gandhara and modern Pashtun lands suggests a direct cultural continuity. The Rubab, with its lute-like construction, is likely a descendant of the short-necked lutes depicted in Gandharan art, as suggested by Sachs

Flutes and percussion instruments also show continuity, with Pashto music preserving the rhythmic and melodic structures seen in Gandharan chants. This connection is further supported by the region's historical role as a musical crossroads, with instruments evolving through cultural exchanges.

Case Study: The Rubab and Its Historical Roots

The Rubab, carved from a single piece of wood like mulberry, has three main strings and sympathetic strings, producing a rich tone. Its playing technique, involving plucking, mirrors the depiction of lutes in Gandharan art, suggesting a historical lineage. In Pashto music, it accompanies ghazals and folk songs, reflecting the continuity of Gandharan musical practices in modern Pashtun culture, as noted in DAWN.COM.

Preservation and Revival Efforts

Recent efforts to preserve Pashto music include documenting oral histories and training youth in traditional instruments like the Rubab, as seen in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa's cultural initiative. These efforts ensure the Gandharan legacy lives on, bridging ancient and contemporary musical traditions.

Conclusion

Gandhara's music, as depicted in its art, was a rich tapestry of cultural influences, with instruments like lutes, flutes, and drums playing pivotal roles in religious and social life. This legacy endures in Pashto music, particularly through the Rubab, reflecting a profound historical continuity. Understanding this connection enriches our appreciation of Gandharan art and Pashto culture, highlighting the enduring power of music to unite past and present, a testament to the region's enduring cultural vitality.

Comentarios