Decolonizing Pashtun history and Identity

- Türán

- 1 day ago

- 5 min read

Why the Colonized Defend Their Captors and how it relate to Pashtun history?

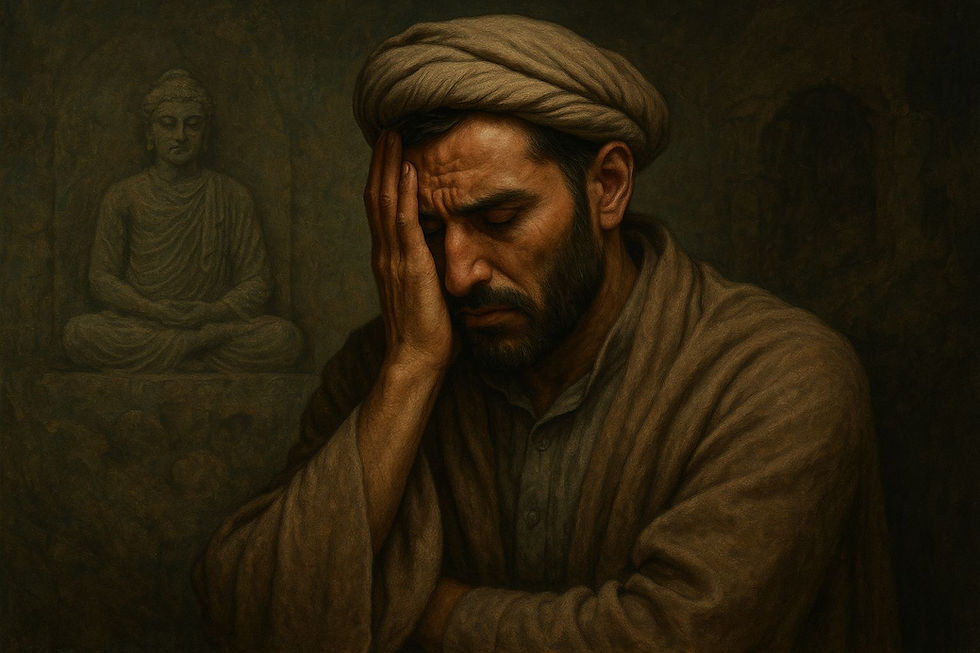

There is a peculiar illness of the soul that afflicts conquered nations long after the conqueror has departed. It lingers not in the ruins or treaties but in the minds of the people; in how they think, what they worship, whom they praise, and what they forget. For the Pashtun people, whose lands span modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan, this condition manifests as a defence of the very forces that sought to erase their names, silence their language, and reshape their dreams. This article explores the deep-seated psychological and cultural impacts of colonialism on the Pashtun identity, delving into the historical invasions that shaped their lands, the psychological mechanisms that perpetuate colonial legacies, and the power of remembrance as a form of rebellion. It invites readers to join initiatives like NeoGandhara, which seek to reclaim and celebrate Pashtun history and heritage.

A Pashtun History of Invasion

The Pashtun lands, a crossroads of civilizations, have endured centuries of foreign conquest, each leaving an indelible mark on their cultural and linguistic fabric.

Alexander’s Invasion (330–327 BC)

In 330 BC, Alexander the Great invaded the region, then part of the Persian Empire, facing fierce resistance from local tribes led by figures like Bessus and Spitamenes. His campaign, marked by brutal battles and the founding of cities like Alexandria in the Caucasus, was a testament to the region’s resilience. Despite his victories, Alexander’s control was tenuous, with local revolts challenging his authority (Warfare History Network).

Arab Conquests and Islamization (7th–12th Centuries)

The 7th century saw Arab invasions that introduced Islam to the Pashtun lands. The capture of Herat in 642 AD marked the beginning, but full Islamization took centuries, culminating under the Ghaznavid and Ghurid dynasties between the 10th and 12th centuries. This gradual process involved both voluntary conversions and pressures from rulers, fundamentally altering the region’s religious and cultural landscape (Wikipedia - Muslim conquests of Afghanistan).

Mongol Devastation (1219–1221)

In the 13th century, Genghis Khan’s Mongol invasions devastated the Khwarazmian Empire, including parts of Afghanistan. Cities were razed, and populations decimated, leaving a legacy of destruction that disrupted the region’s cultural continuity (Wikipedia - Invasions of Afghanistan).

British Colonial Rule (19th Century)

The British Empire’s interventions in the 19th century, driven by the Great Game to counter Russian influence, had profound effects. The First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842) ended in disaster, with the 1842 retreat from Kabul resulting in the massacre of nearly the entire British army. The Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–1880) led to the Treaty of Gandamak, granting Britain control over Afghanistan’s foreign affairs. The 1893 Durand Line further fragmented Pashtun territories, sowing seeds of division that persist today (Wikipedia - First Anglo-Afghan War; Wikipedia - Durand Line).

These invasions did not merely conquer land; they reshaped identities, languages, and memories, embedding a colonial mindset that lingers in the Pashtun psyche.

The Psychology of Submission: Colonial Mentality

The brilliance of colonialism lies in its ability to survive beyond physical occupation, residing in the minds of the colonized. Postcolonial theorists Frantz Fanon and Albert Memmi describe this as a “colonial mentality,” where the colonized internalize feelings of inferiority and adopt the colonizer’s values (Fanon, 1963; Memmi, 1965). Fanon argues that colonialism’s systematic denial of the colonized’s humanity leads to self-doubt and identity confusion, while Memmi notes that the colonized may adopt identities aligned with the colonizer’s stereotypes.

This phenomenon, likened to Stockholm Syndrome, where captives bond with their captors, explains why some Pashtuns may defend colonial legacies. The imposition of foreign governance systems, religions, and languages created a fractured identity, where native traditions were deemed inferior. For instance, during British rule in the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP), Urdu was promoted as the administrative language, marginalizing Pashto and distancing Pashtuns from their linguistic heritage (Criterion Quarterly).

Cultural and Linguistic Erosion

Colonialism’s impact on Pashtun culture was profound, particularly in the erosion of the Pashto language. Under British rule, Urdu was favored in NWFP to integrate the region into British India and distance it from Afghanistan, where Pashto was dominant. This policy relegated Pashto to a secondary status, limiting its use in education and administration (BritishEmpire.co.uk). The marginalization of Pashto contributed to a broader cultural disconnection, where Pashtuns were taught to view their language and traditions as less valuable.

It was not until the 1920s that Pashtun leaders like Abdul Ghafar Khan sought to revive Pashto through initiatives like the Anjuman-e-Islah al-Afaghina, promoting it as a symbol of Pashtun identity. This movement, attended by thousands, marked a resistance against colonial linguistic suppression (Wikipedia - Pashto).

Aspect | Pre-Colonial Status | Colonial Impact | Post-Colonial Revival |

Language | Pashto as primary language of Pashtuns | Urdu promoted; Pashto marginalized | Efforts by Abdul Ghafar Khan to promote Pashto |

Cultural Practices | Pashtunwali as guiding code | Colonial stereotypes of Pashtuns as “violent” | Revival through cultural societies |

Territorial Unity | Unified Pashtun lands | Divided by Durand Line | Advocacy for Pashtun unity (e.g., PTM) |

Remembrance as Rebellion

To speak of Gandhara, of Pashto’s ancient roots, and of the pre-colonial Pashtun identity is not merely to recount history; it is to rebel against the colonized mind. Remembrance challenges the narratives imposed by conquerors, fostering a reconnection with authentic cultural roots. The Gandhara civilization, a cradle of art and spirituality, represents a heritage that predates foreign invasions, offering a source of pride and identity (X - NeoGandhara).

Initiatives like NeoGandhara are at the forefront of this rebellion. Through social media and community engagement, NeoGandhara celebrates Pashtunwali’s values; honor, hospitality, and justice; and highlights cultural treasures like the Attan dance and Pashto music. By countering misconceptions that portray Pashtuns as inherently violent, NeoGandhara fosters a decolonized identity rooted in pride and resilience (X - NeoGandhara).

Conclusion: An Invitation to NeoGandhara

The journey to unchain the Pashtun mind from colonial shackles is ongoing. It demands a rejection of internalized oppression and a celebration of indigenous heritage. NeoGandhara invites you to join this movement, to explore the rich history of the Pashtun people, and to contribute to a future where cultural pride triumphs over colonial legacies. By remembering and reclaiming our roots, we transform history into a tool for liberation.

Join us at NeoGandhara to rediscover the soul of Pashtun identity, from the melodies of the rabab to the fierce grace of the Attan. Together, we can honor our past and shape a future free from the shadows of conquest.

Great article! It really highlights the importance of reclaiming Pashtun identity and culture after centuries of colonial impact. Proud to see NeoGandhara leading this important movement.