Gandharan Buddhism

- Türán

- May 15

- 3 min read

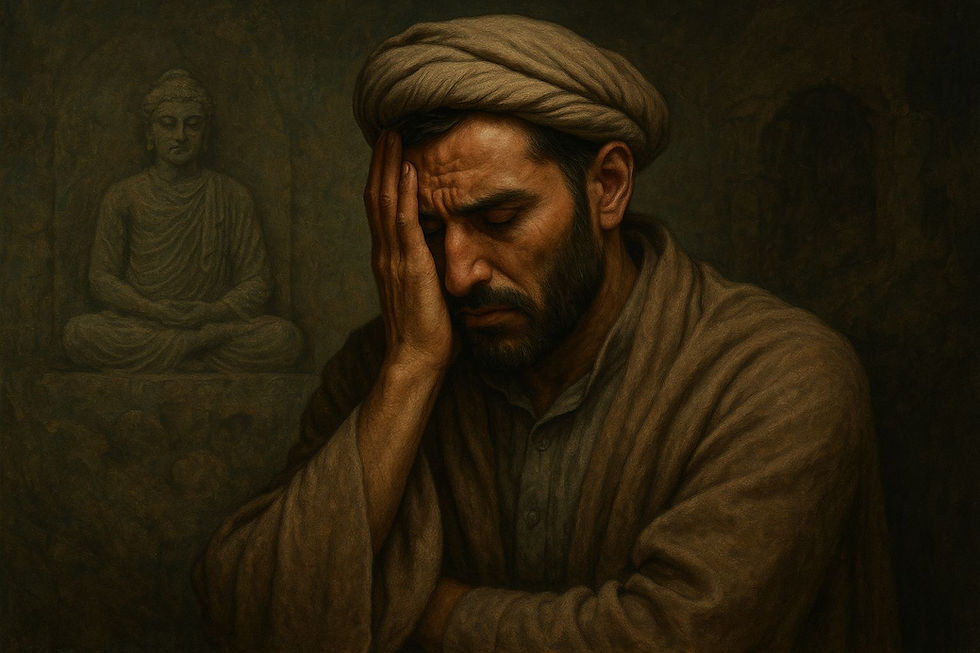

Gandharan Buddhism The Forgotten Light of the Frontier

Gandharan Buddhism was not a foreign arrival. It was a spiritual blossoming rooted in the soil of the northwest subcontinent. Between the 3rd century BCE and the 7th century CE, Gandhāra became one of the most sophisticated and cosmopolitan centers of Buddhist thought in the ancient world. Its borders included cities such as Takṣaśilā, Puruṣapura, Uddiyāna, Bagram, and Kapisa. These were not peripheral outposts. They were thriving capitals of education, sculpture, trade, and meditation.

Gandharan Buddhism flourished during the reign of Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya dynasty in the 3rd century BCE. Ashoka’s patronage spread Buddhism widely across his empire, and Gandhāra became a vital transmission point for the Dharma. Later, during the reign of the Kushan Empire from the 1st to 3rd century CE, the region entered its golden age. Under King Kaniṣka I, who ruled around 127 CE, Gandhāran Buddhism received imperial support, and Takṣaśilā evolved into one of the earliest university cities in the world.

This environment gave rise to some of the most influential Buddhist philosophers in history. Vasubandhu and his elder brother Asanga, both born in Puruṣapura, laid the foundations for the Yogācāra school of Mahāyāna Buddhism in the 4th century CE. Yogācāra, or the Mind-Only school, proposed that the world we perceive is a construction of mental impressions shaped by karma and intention. It introduced the concept of ālaya-vijñāna, or storehouse consciousness, where all experiences are subtly recorded and later manifest as perceptions or thoughts. This school emphasized the transformation of consciousness through study, meditation, and moral discipline.

To revive Gandhāran memory is not to idealize the past, but to acknowledge the extraordinary fact that a frontier once lit the intellectual fire of half the world.

The core teachings of Buddhism were preserved in Gandhāra, but they were not taught as abstract doctrines. The Four Noble Truths formed the ethical base: that suffering exists, that it has causes, that it can end, and that there is a path to its cessation. The Eightfold Path outlined a practical guide to this liberation, including right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration.

Gandhāran Buddhism was deeply visual. It was in this region, during the 1st century CE, that the Buddha was first represented in human form. Earlier traditions avoided depicting him anthropomorphically. Under the influence of Greco-Roman art brought through Alexander’s eastern campaigns, Gandhāran sculptors created serene, naturalistic images of the Buddha in stone and stucco. These images became standard across Asia. Many of them were created in monasteries such as those at Jaulian, Mohra Muradu, and Takht-i-Bahi. Their influence stretched as far as China and Japan.

Monasteries in Gandhāra were not merely places of devotion. They were active learning centers. Students studied logic, medicine, grammar, metaphysics, and languages including Sanskrit, Prakrit, Pali, and Bactrian. The university at Takṣaśilā, active from at least the 5th century BCE, attracted scholars from across Asia. The Chinese pilgrim Faxian visited the region in the early 5th century CE, and Xuanzang followed in the 7th century. Both described Gandhāra as a land of towering stupas, disciplined monks, and profound learning.

This flourishing culture was eventually dismantled by waves of invasion beginning in the 6th century CE, including the destructive campaigns of the Hephthalites and later Islamic conquests. Monasteries were destroyed, texts were lost, and statues were defaced or melted down. Yet even after physical destruction, the spiritual and intellectual legacy of Gandhāran Buddhism lived on. The teachings of Vasubandhu and Asanga were preserved in Tibetan and East Asian traditions. Gandhāran manuscripts, some of the oldest surviving Buddhist texts, were rediscovered in the 20th century in clay jars in what is now Afghanistan and northern Pakistan.

Gandhāran Buddhism teaches us something essential. That wisdom is not owned by any nation or era. It reminds us that truth can flourish in mountain valleys and along trade roads. That art, logic, compassion, and breath can live together in one civilization. To revive Gandhāran memory is not to idealize the past, but to acknowledge the extraordinary fact that a frontier once lit the intellectual fire of half the world.

Comentarii